Leonard Cohen surely had the strangest career arc (and quite possibly the most fascinating and adventurous life) of any significant modern musician. When he recorded his first album in 1967 he was already 33 years old. He was not just a newcomer to the music industry - he was a newcomer to the world of music itself. He had learned to play a little bit of guitar in his teens but he certainly never considered himself a musician. Cohen was a writer with an established reputation, the author of two novels and four volumes of poetry. In Canada he was already relatively famous, having somehow achieved a degree of celebrity seldom granted to poets. In 1967, a collection of his Selected Poems won the Governor-General's Award and came as close to being a best-seller as a book of poetry can possibly come. (My father was one of those book-buyers - he admired the poems, and they certainly made a large impression on me.) It turns out now that Cohen was just getting started.

Like Mordecai Richler, Cohen was an English-speaking Jew in the largely French and Catholic city of Montreal - but Richler came from a different side of the tracks, the working class neighborhood of St Urbain Street that he would revisit in his novels. Cohen grew up in Westmount, the son of a tailor. All his life, Cohen's taste for fine clothing was impeccable - as he told his biographer Sylvie Simmons "Darling, I was born in a suit." His literary career had begun while he was an undergraduate at McGill University. There was a thriving local poetry scene, whose senior figures included Cohen's own teacher Louis Dudek. Also teaching at McGill was Irving Layton, perhaps the first significant poet to have emerged in Canada, and a man who would become Cohen's lifelong friend and mentor. "I taught him how to dress and he taught me how to live forever" Cohen would one day remark. Layton and Dudek were on the editorial board of CIV/n, a tiny local magazine, which was where Cohen's first poems to appear in print were published in 1954.

Cohen graduated in 1956; his first slim volume of poems Let Us Compare Mythologies, had been published earlier in the year. He set off for New York for a year of graduate school at Columbia, but by 1958 he had begun two pursuits that would occupy much of his next forty years: restless travelling, from one locale to another (and one woman to another), often circling back to familiar haunts (and always back to Montreal) but seemingly never able to settle anywhere for long; and fighting off recurring bouts of depression, which he would describe as "a kind of mental violence which stops you from functioning properly from one moment to the next." He wandered overseas, first to London, then Israel, then Greece. He heard about a small island called Hydra, and armed with a $1500 inheritance bought a house there in 1960. There was no electricity and no running water. Cohen, who all his life had a deep fondness for spartan ways of living, loved it. He spent much of the 1960s there, writing some of his most famous works, and the house has been passed down to his children.

Along with his poems, Cohen had been attempting to write a novel. His first attempt did not find a publisher, his second was never finished. But his second book of poems, The Spice Box of Earth, published in 1961, was very well received and extended his reputation beyond the Montreal circle he had come from. He was still working on a novel, while alternating his base of operations between London and Hydra, and in 1963 The Favourite Game was published in the UK, with US publication the following year. It was very much an autobiographical work, or at the very least one in the Joycean tradition of creating a self-serving mythos around one's own experience. Notices were very positive on both sides of the Atlantic, although his Canadian publisher waited for seven years before finally issuing it in his own country. Jack McClelland had signed Cohen personally, but as a poet, and he seemed to have trouble dealing with the idea of him as a novelist.

A third book of poems, Flowers For Hitler, appeared in 1964 and in the same year he became the subject of a film by Donald Brittain, Canada's most noted documentarian. Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr Leonard Cohen, is both a fly-on-the-wall study of Cohen's life in Montreal and an affirmation of his growing visibility on the Canadian cultural scene. The man himself was back on Hydra, finishing a second novel. Beautiful Losers - described by its author as a "disagreeable religious epic" - was published in the spring of 1966. Nothing like it had ever been published in Canada. Its nominal story concerns a scholar in love with a long-dead young Indian woman from the 17th century - it is also a hallucinatory quest for sex, salvation, and history. It dazzled, disturbed, and often disgusted its readers in equal measure. It was followed a few months later by a fourth volume of poetry, Parasites of Heaven. But for all his fame and his fine reviews, he was having trouble paying his rent.

He had a small inheritance and was living half the year in the house on Hydra, which he thought was a fine way to live. But he couldn't get by on a poet's royalties. He was constantly going back to Montreal, taking odd jobs, and hustling for Canada Council grants and other types of support. After the intense and extreme experience of writing his second novel, a product of truly epic consumption of amphetamines and all sorts of psychedelics, he decided to go to Nashville. He had formed the mad idea that perhaps he could write some songs and make a little money that way. At least, that's the story as Cohen himself always liked to tell it. His interest in becoming a songwriter seems actually seems to have developed by degrees, although his personal financial needs were always the primary motivating force.

I couldn't make a living as an author. My books weren't selling. They were receiving very good reviews but my second novel Beautiful Losers sold about 3,000 copies worldwide. The only economic alternative was, I guess, going into teaching or getting a job in a bank.... But I always played the guitar and sang, so it was an economic solution to the problem of making a living and being a writer.

His plan was to go to Nashville and become a songwriter. He never made it there. He stopped first in New York, and there he was put in touch with Judy Collins.

Joan Baez was undoubtedly the reigning queen of early 1960s folk music, but Judy Collins was the next best thing. Both women had started out at the beginning of the decade singing songs from the traditional folk repertoire. After a few albums of this both women were looking for newer songs to sing. Bob Dylan was an obvious source for such material, and Baez - far more interested in politics, drawn first to Dylan's early topical songs, and soon enough to the man himself - had a kind of prior claim. Collins recorded Dylan tunes as well, but she was more musically ambitious than Baez, and more interested in other contemporary songwriters. As Baez simply added more and more Dylan songs to her repertoire of traditional songs, Collins' 1966 album In My Life had a Lennon-McCartney song for its title track and also included songs by Randy Newman, Donovan, and Jacques Brel, as well as two songs by a Canadian poet not known to be a songwriter at all. One of those songs was called "Suzanne."

Until "Hallelujah" surprisingly became absolutely ubiquitous some thirty years later, "Suzanne" would always be Cohen's most famous song. At this remove it's necessary to remind ourselves just how strange and different it was from everything else at the time. Its first verse seems to describe a night with a woman named Suzanne, although it doesn't seem to be a love song at all. It seems to say much more, in very precise terms, about the setting for this encounter than the woman. The second verse changes the subject completely, imagining Jesus as a sailor who eventually disappears beneath the waves. The last verse takes us back to Suzanne again. Nothing much seems to happen, but it's all described in vivid, memorable images and set to a graceful and somehow inspiring melody. (Cohen would eventually explain that much of it was simply drawn from life. Suzanne was the wife of an old friend, she lived in a part of old Montreal near the river, she really did serve guests that kind of tea. Our lady of the harbour is a statue of the Virgin Mary atop a local church.)

No one in 1966 has ever heard anything like this in a pop song. Only Bob Dylan was writing lyrics of such quality and ambition - but Cohen's lyrics didn't much resemble Dylan's at all. Dylan's literary antecedents (at that time) were quite clearly the American Beat writers, Kerouac and Ginsberg in particular. Dylan shared their fondness for rambling, free-associative narratives. Cohen liked the Beats (they didn't much like him, finding him rather old-fashioned) and their influence can be seen in some of his poetry, especially when he was engaged in satire or humour. Cohen was a twentieth-century poet, and like Eliot or Williams often used the freer verse forms seen in so much of his own time's poetry. But at heart, he was a modern lyric poet - his great hero was Federico Garcia Lorca - and like Lorca, Yeats, and Baudelaire he especially liked to use the most traditional verse forms and load them with the most modern possible content and themes. In his song lyrics as well, Cohen honoured these more traditional literary traditions and forms, in the ways his lines scanned, in the rhymes he chose, and the images he utilized. They were clearly the work of an educated, experienced poet, part of a literary tradition.

Cohen himself began to consider much more seriously the possibilities of music as a career path. Collins had been taking up Cohen's work to all her friends in the industry; she also managed to persuade a reluctant Cohen into performing them himself. Collins recorded three more of his songs on 1967 album Wildflowers (which also saw the first recordings of songs by Cohen's one-time lover and compatriot Joni Mitchell.) John Hammond (who else) eventually heard him, and instantly decided he needed to be a Columbia artist. Despite the usual resistance from the company that all Hammond's projects seemed to encounter, he was able to sign Cohen to Columbia records. In May 1967, he began to record his first record.

Cohen would release fourteen collections of his songs over the next half-century, the last one appearing just three weeks before his death in November 2016. His son Adam would finish a final set of songs, issued in 2019. As he aged, the intervals between records often got longer and longer as he pursued his many other interests, in particular his other literary projects and his endless investigations into various roads to enlightenment. But in his old age, an unexpected financial crisis once more prompted him into action, spurring him to a remarkable burst of creativity in the final decade of his life, which also saw him emerge, somewhat surprisingly, as a wonderfully engaging performer of his own work.

This was not a development anyone could have foreseen. When he was a young man, Cohen sang his songs in a strangely flat and unaffected monotone, accompanying himself with his somewhat rudimentary guitar playing. (As a guitarist, Cohen had three basic finger-picking patterns that he used over and over - two of them, easy enough for any beginner to master, simply depended on whether the song was in 3/4 or 4/4. He also had a somewhat more tricky flamenco pattern that a neighbour taught him, used on special occasions, as in "The Stranger Song.") Cohen once noted that he didn't believe his own music was particularly depressing - "my voice just happens to be monotonous and I'm somewhat whiney... but you could sing them joyfully too." As he would eventually prove himself.

His voice changed considerably over the years - it deepened to such a degree that he was forced to change the keys of many of his old songs if he still wished to perform them. Not being up to the task of actually transposing his songs into a new key, Cohen simply tuned his guitar lower and lower and lower so that he could continue playing them the same way he always had. But Cohen always had charisma to burn. Over the years, he would issue eight live collections: two of these were historical documents of famous performances that had taken place decades earlier. The rest all caught him in the moment, and while every one of them is well worth your acquaintance, 2009's Live in London is especially noteworthy, a magnificent overview - and a joyous celebration - of a remarkable career.

He was a small, slim man with beautiful Old World manners - he practically made a fetish of being modest and courteous. He was a restless explorer, of faiths and philosophies. He was an incorrigible joker, a minor poet, an interesting novelist, an unwilling performer for most of his life, and as great a songwriter as ever lived.

There's a natural enough tendency to divide Cohen's musical career into two parts: the first and biggest part would cover the years before he discovered that his manager had made off with his life savings, the second part would be his glorious final act. That makes a kind of biographical sense, but I think a better dividing line is 1988's I'm Your Man. That's because I think that's where, at the age of 53, after releasing seven albums in his two decades as a recording artist, Cohen finally discovered the best way for him to record his own songs.

15. Death of a Ladies Man (November 1977)

This was an experiment that didn't work. Joni Mitchell tried to warn Cohen about Spector, who had recently proved himself too crazy to work with John Lennon (during his LA Lost Weekend.) Apparently, everything went rather smoothly when they were sitting in Spector's chilly mansion, writing songs at the piano. It was when they got into the studio that the trouble started. The settings for these songs represent the last worthwhile work of Spector's career, but Cohen as a singer was uniquely ill-suited to these type of arrangements. Spector's music usually fills every available audio space - the singer, whether it be Ronnie Spector or John Lennon, has to either find a way to be heard over it or find their own place as a part of that whole. This would never suit Cohen's vocal methods - Cohen needs his own room in the music, he needs to find spaces he can sing through. The overall madness of Spector's working methods obviously made things even worse.

14. Dear Heather (October 2004)

This sounded like a great old artist fading into the distance. He begins by setting a famous lyric by Lord Byron and closes with a live cover from 1985 of "Tennessee Waltz." At the centre of the album is a spoken word track, a recitation of F.R. Scott's "Villanelle for Our Time" with musical accompaniment. Several tracks provide setting for poems published decades earlier. Fading into the distance, tying up a few loose ends. And then he discovered that his long-time manager had embezzled his retirement fund and sold off his publishing.

13. Songs From a Room (March 1969)

Do not be deceived by its comparatively low ranking - this, like all the others placed above it, is a fine record, with songs far beyond the capacity of most of the songwriters who have ever walked the earth. Cohen's original musical plan had been to go to Nashville and become a songwriter. This was when he actually got there, with Bob Johnston at the controls. Unfortunately, most of the songs simply aren't as compelling as the ones on his debut. This of course is the record that includes "Bird on the Wire," one of the most celebrated (and covered by other singers) songs of his career. Alas, I no longer think all that highly of the song, which seems somewhat cliched (and devoid of real melody) by Cohen's standards (although, from time to time, I do find myself loving it as deeply as I ever have!) But the little known "Story of Isaac" is stunning, one of the most remarkable songs written by anyone, ever. This record also includes his haunting cover of "The Partisan," a song he would continue to perform in concert through his entire career.

He looked once behind his shoulder

He knew I would not hide

You who build the altars now

To sacrifice these children

You must not do it anymore

A scheme is not a vision

You never have been tempted

By a demon or a god

12. Recent Songs (September 1979)

After the Spector misfire, Cohen got back to sounding like Leonard Cohen again. This time he listened to Joni Mitchell, who suggested he try working with her engineer/producer Henry Lewy. The musical setting are much more sympathetic, and for the first time Cohen makes a great deal of use of female voices to support his own. It's very much a return to form, with a collection of fine songs. My sole reservation is that it's the one Cohen album (along with the Spector mistake and the Dear Heather oddity) that doesn't have any great songs, although "The Traitor" does come mighty close. Cohen always thought highly of this record himself, and "The Gypsy's Wife" would stay in his concert repertoire for the rest of his life.

this is the darkness,

this is the flood

And there is no man or woman who can't be touched

But you who come between them will be judged

11. Songs of Love and Hate (March 1971)

Cohen's third album showed signs of strain. He was in a state of deep depression and seemed to be getting tired of the sound of his own voice. He did not want to make a third album and didn't believe he could. There were only eight songs, and half of them came from the trunk, having been written years earlier. The writing is remarkable, but there's what seems almost like a shortage of energy in the performances. Which seems like an odd complaint to make of Cohen, but on much of this it seems like he barely has the strength to sing. What it really betrays is an acute dearth of melodies to sing, so he picks his guitar and more or less recites. It all imparts a certain sameness to the proceedings, as if the songs are somehow extensions of one another, rather than individual entities: despite the fact that the subject matter of one has nothing to do with that of the next. That said, the writing is extraordinary - the closing "Joan of Arc," as the doomed martyr confronts the flames is astounding. And even the overall musical malaise lifts when Cohen unfolds the compelling tale of the triangle of friends and lovers recorded in "Famous Blue Raincoat," set to what is by far the finest melody here.

What can I possibly say?

I guess that I miss you, I guess I forgive you

I'm glad you stood in my way

10. New Skin for the Old Ceremony (August 1974)

On his fourth studio album (he'd issued a live placeholder in the interim), with the assistance of co-producer John Lissauer, Cohen finally began to expand on the basic sound of his music. Everything is still based on his always rudimentary guitar, but the tracks are adorned with Lissauer's assorted instruments (keyboards and woodwinds), Lewis Furey's viola, Jeff Layton's mandolin and banjo. Even better, each of the song has its own very distinctive character, a very welcome development after the overall sameness that had troubled Songs From a Room and Songs of Love and Hate. Cohen is also beginning to stretch himself - just slightly - as a singer. The ferocious "Is This What You Wanted" opens proceedings by positing a series of impossible oppositions ("You lusted after so many / I lay here with one") and ends with Cohen almost snarling the chorus. "Lover Lover Lover," for the first time (but definitely not the last) sounds more like the work of some strolling European cafe singer than anything from the North American musical traditions. Cohen would always regret the indiscretion that had identified Janis Joplin as the woman he shared a moment with in the Chelsea Hotel, but the song itself, graphic details and all, is one of Cohen's greatest, and a tribute one hopes (and suspects) would have made her very proud indeed to have inspired.

I need you,

I don't need you,

I need you,

I don't need you

And all of that jiving around

9. Thanks For the Dance (November 2019)

This collection of songs left in various stages of completion at the time of Cohen's death was finished by his son Adam with the assistance of numerous luminaries, including Beck, Damien Rice, Leslie Feist, and Daniel Lanois as well as Cohen's own old collaborators Sharon Robinson, Jennifer Warnes, and Patrick Leonard. There are a few songs that are really spoken word pieces with musical accompaniment (they manage to work on their own terms anyway.) The overall result is somewhat slight (just 29 minutes) but still very much worth the effort. As usual, it's the highlights that make it so - "Night of Santiago," "Happens to the Heart," and especially "Moving On."

As if there ever was a you

Who held me dying, pulled me through

Who's moving on

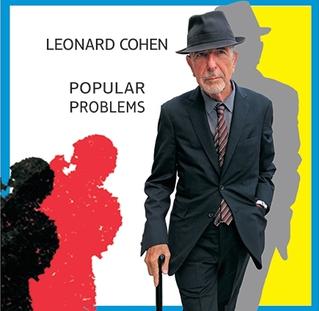

8. Popular Problems (September 2014)

Released the day after his 80th birthday, this collection followed the tour in support of Old Ideas, which saw him play another 125 shows in 16 months, ending in December 2013. It could not be known at the time that he would never again perform in public. To my mind, this one is a little like Recent Songs - it's a solid record, with a bunch of good and interesting songs. It simply doesn't have any great songs.

And there's all my bad reviews

The war, the children missing,

Lord, it's almost like the blues

7. Various Positions (December 1984)

This outstanding work is very much a transitional record. And Columbia declined to release the album in the US. Label president Walter Yetnikoff would famously tell Cohen ""Look, Leonard; we know you're great, but we don't know if you're any good." It had been five years since Cohen's previous record, the longest gap between new records to that point in his career. He had been working (slowly, as always) on a new book of poetry. He was generally in motion, moving between Montreal (as always) and Los Angeles, the south of France (where his children lived) and Hydra. He had purchased a cheap Casio synthesizer and begin using it instead of the guitar to write his new songs. The different musical settings he was generating with his little synthesizer were beginning to broaden the general musical palette beyond what his limited guitar tricks could provide. And in his mid-forties his voice was beginning to change. Most obviously, his pitch had dropped to a considerable degree. But something else about it had changed as well. Cohen's voice had always had a kind of naked quality to it, a kind of flat amateurishness that was itself part of its appeal. There was no guile to it whatsoever, by which I mean there never seemed to be any recourse to the many singer's techniques available to deliver the song. There was only ever this naked human voice. But now, as he aged, it was somehow acquiring additional textures as its pitch deepened and its range narrowed.

But even more to the point, we find here some of the greatest songs of his career, in particular the three that would be fixtures in his performance repertoire for the rest of his life. The first, the opening "Dance Me to the End of Love" is practically a musical assertion that there's a new sheriff in town. It begins with the Casio's cheap drum track, a steady bass, women la-la-ing away, Lissauer's keyboard settings - while Cohen sings words originally inspired by the presence of a string quartet at the Nazi death camps (that's not what the song turned out to be about, of course.) No one else, man. And it closes with one of the most remarkable compositions of this author's exceptional career, the exquisite prayer "If It Be Your Will" which is somehow both infinitely delicate and stunningly powerful. All at once. And then there's "Hallelujah."

It is, as all the world would come to realize, a very great song indeed. It took a long time to reach its initial form, as heard on this album. Cohen was actually embarrassed by how long he'd spent on the writing of it. When Bob Dylan asked him, he lied and said "Two years." He would later confess to writing more than 80 verses, kneeling on the floor in his underwear and banging his head in frustration. And the song would take even longer to finally evolve into the version best known today. Here, in its first appearance, the song has four verses, with Cohen accompanied mainly by a polite rhythm section, Sid McGinnis' electric guitar, and swelling female voices. But when he started performing it on his 1988 tour, three of those original verses had been jettisoned and new ones had taken their place. Only the concluding verse remained from the original recording.

This was the version John Cale heard Cohen perform. Cale wanted to record his own version and asked if Cohen could send him the lyrics. Cohen famously sent him a 15 page FAX containing many of those 80 verses originally written and Cale created his own version of the song from the ones he liked best. He took the first two verses from the 1984 record, the first three verses from the 1988 concert version, and dropped the closing verse - which was the only verse Cohen himself had been singing all along.

Cale's version appeared on a 1991 Cohen tribute album, and it was Cale's version that was the basis of Jeff Buckley's stunning 1994 cover on Grace. Buckley's version, with its haunting guitar work and Buckley's unforgettable vocal performance - his voice was one of the more miraculous things anyone will ever hear - became a popular choice to grace the soundtracks of numerous film and television programs. The Cale-Buckley choice of verses would emerge as the canonical version of the song, and when Cohen resumed performing it, twenty years after its original recording, he would sing the same verses they had settled on as the song's ideal form. But Cohen always added his own original closing verse, that both Cale and Buckley had omitted.

The song has always held an irresistible attraction to other singers. The melody is so graceful and enticing, the words are so strange and so compelling - and there's so much space in the music for the singer to insert his or her own personality, a temptation almost no singer who has ever assayed the song has been able to resist. And hence in many ways its performance always becomes about the singer rather than the song. It becomes a demonstration of what a singer can do with a song. In the case of a great singer like Jeff Buckley one probably doesn't mind too much. But it's why I have to think that the definitive versions of the song are the performances by its own author on his late life concert tours from 2008 onward. If there was one singer in the history of music completely immune to the temptations of showing off one's vocal prowess, that singer was Leonard Cohen.

And bind us tight

All your children here

In their rags of light

In our rags of light

All dressed to kill

And end this night

If it be your will

6. You Want It Darker (October 2016)

The last album Cohen released in his lifetime was recorded at his laptop in his living room, with the essentially immobile artist singing from a medical chair and exchanging emails of the backing tracks with his collaborators. The visibly frail artist, 82 years old, then appeared at a press conference upon its release. Though clearly a little short of breath, he assured his assembled guests that the rumours of his imminent demise were exaggerated and that he intended to live forever. He died in his sleep three weeks later, which rather surprisingly didn't really change the way this record was heard. Cohen had always been old, he had always written from a vantage point of maturity, certainly in comparison to the rest of the popular music world, and he had always dwelt on these kind of questions. Asked at the time about the place religion had in his life and work, he said he had no spiritual strategies he could recommend. He had, however, grown up with a certain vocabulary and was comfortable using it. Here we find affairs that are to be set in order, last statements of protest and defiance to be filed. And so in the title track, we hear him singing from the Torah, "Hineni, Hineni (Here I am) - I'm ready my Lord." It has little time for the usual jokes, and little time for many of the old obsessions - "I don't need a lover / That wretched beast is tame." And it would certainly be dishonest to go into that dark night and pretend that there are no regrets, which is the theme of "Treaty," which gives us one last beautiful melody from a writer whose gift for melody was always overlooked.

It's over now, the water and the wine

We were broken then, but now we're borderline

I wish there was a treaty

I wish there was a treaty

Between your love and mine

5. Songs of Leonard Cohen (December 1967)

Cohen's debut was an extremely unusual project. It's one thing for the artist to have never been in a recording studio before. This artist had never played with professional musicians before; he had seldom even performed in front of people at all. John Hammond set out to produce it himself, and Cohen developed a musical rapport with a bass player named Willie Ruff, but when other musicians were added to the mix everything ground to a halt. Hammond eventually dropped out and John Simon took over production duties, and his ultimate solution was simplicity itself. Simon recorded Cohen singing to his own guitar accompaniment, and overdubbed various things to season the tracks, often in strange ways. Various instruments seem to enter and depart at random on "So Long Marianne;" "Master Song" is punctuated first with what might be a muted trumpet, then a tremolo guitar, then a violin, a bit of organ. It's remarkable that it all works as well as it did - but there's a simple enough reason. If there's another songwriter's debut that has songs of this quality, I haven't heard it. "Suzanne" is the most famous track, and no wonder, but it has plenty of company: "Hey, That's No Way to Say Goodbye" is simply gorgeous and "So Long Marianne" is irresistible. "The Stranger Song" is mysterious, compelling, haunting - and the performance is remarkable, Cohen's careful, sensitive vocal accompanied only by his own flamenco guitar picking. It closes with "One Of Us Cannot Be Wrong" (a phrase that has haunted me forever - it means that one of us must be), which calmly outlines various ways of going insane from love and closes with weird atonal moans and cries and whistles as the guitar peacefully repeats the song's pattern. Nothing like it, to this day.

He'll say one day you caused his will

To weaken with your love and warmth and shelter

And then taking from his wallet

An old schedule of trains, he'll say

I told you when I came I was a stranger

4. The Future (November 1992)

This builds upon the musical directions firmly established on its predecessor, and includes several of his greatest tunes. It goes off the rails a bit at the end, with its lengthy cover of Irving Berlin's "Always" and the closing instrumental "Tacoma Trailer." But the first two-thirds of the record is remarkable, and the highlights: the title track, "Closing Time," "Anthem", and "Democracy" are among the finest achievements of his career. The subject matter is generally apocalyptic, a disturbing vision of a culture in irreversible decay, described by the artist with a kind of savage glee. He's seen the future, brother. It's murder. It's a record of lengthy rants against what the world has become, leavened mainly by the poet's always memorable wordplay, and the general mood of being cheerfully entertained by it all. "Closing Time" seems to regard the end of civilization as the final moments of a memorable party. Yet against all the images of doom and decay, "Anthem" actually seems to posit reasons to resist, reasons to find the struggle worth pursuing, and of course it includes what may be the most celebrated lines he ever did write.

3. Old Ideas (January 2012)

The theft of his savings ultimately forced him out of his comfortable semi-retirement and back on the road, Touring had always made him uneasy - it had always felt like something forced upon him by the need to promote his latest entry into the world of musical commerce. He always found it a somewhat disorienting strain, and he had always coped by fortifying himself with liberal applications of drugs and liquor. His last experience, touring behind The Future in 1993, had driven him to a monastery for five years. Now, in his old age, he had no new record to sell - just children he hoped to provide for, along with his own retirement. But he had gained a new kind of equanimity and went to meet whatever audience he still had clear-eyed and clear-headed. He was still so unsure about his ability to make it work that he insisted on first doing a warm-up tour of 18 dates in eastern Canada, mostly the Maritimes. But he found himself born again, as a road warrior of all things. Cohen played 347 shows over the next three years, and for the first time in his career greatly enjoyed the experience. He was deeply moved to discover that there was indeed still an audience eager to hear him.

The whole experience seemed to energize him - he would produce three albums of new songs in the final four years of his life, beginning with this one. It opens with the voice of God himself having a word with the poet, delivering some instructions, and noting that none of this is negotiable. Best to get on with it. Which he does - he provides a couple of extraordinary tunes that are actually based on blues forms, "Darkness" and "Banjo," the rueful confession of "Crazy To Love You," the purpose and determination of "Show Me the Place." As remarkable as so much of this music is, it all pales alongside the delicate, serene "Come Healing" - a piece of music so profound, and so exquisitely beautiful that merely talking about it seems pointless.

The penitential hymn

Come healing of the spirit

Come healing of the limb

2. Ten New Songs (October 2001)

The tour supporting The Future left Cohen in an uncertain state. Like the album, it had been well received. But he had never been particularly comfortable with the touring life, and the scheduling of this one, and the pressures it inflicted on everyone involved troubled him deeply. All the while his relationship with Rebecca de Mornay was coming to an end. His response was to drive away from the world and live in a monastery, in Mount Baldy just north of Los Angeles. It would be thirteen years before he made his next public appearance. He would spend the next five years as the personal servant and companion of Roshi, an elderly Japanese monk Cohen had taken as a personal master. Cohen himself would be ordained a Zen Buddhist monk in 1996, and given a new name - Jikan. He never found any of this incompatible with his lifelong commitment to Judaism - he continued to observe the sabbath - nor his future interest in Hindu thought. But after five years on the mountaintop, he was suddenly overcome by panic and despair, and took leave of his aged master. He did not return to the life he had left behind - he was off to India, to study with Ramesh Balsekar the Advaita master. And upon his return - first to Mount Baldy to visit with Roshi, and then back to his life in Los Angeles - the cloud of depression that had hovered over him almost all his life seemed to have blown away. He couldn't explain why, and chose not to look a gift horse in the mouth.

He had been "blackening pages" all along, of course. What was different about this next record was the amount of collaboration involved. Cohen turned everything - the melodies, the settings, the arrangements, the musical performances, the production - over to his two female collaborators. Leanne Ungar did the mixing and engineering and Sharon Robinson did everything else. She had sung with him on his tours back in 1979 and 1980, and had helped write a song on each of two previous albums. Robinson had a sure sense of the types of melodies Cohen liked, and was capable of singing. They also found one another easy to work with, comfortable in each other's company, not really working at all. Everything began with Cohen's words, with musical settings then devised by Robinson. And then they would talk about it all, try different ideas, come to some kind of conclusion.. She would record them by herself at home, and although she expected him to replace her vocals in the end, to bring in real musicians to play the parts she had devised on her keyboards, he chose not to. He thought her settings were what best suited the songs, and he liked singing along with her.

They made a masterpiece together. From the opening "In My Secret Life" - which bleakly catalogues the immense gaps between the world as it is and the world as we would wish it be, and the even greater gap between ourselves as we are and what we like to think ourselves to be - to the bone-deep resignation of the closing "The Land of Plenty" the writing is simply remarkable, both in living up to the high standards of his very best work, and maintaining that quality for the entire record. Obvious highlights are "Boogie Street" (an actual street in Singapore, full of colourful bazaars by day and a sex marketplace by night - here it's simply the real world that keeps intruding on us all); the radiant "A Thousand Kisses Deep" (even more gorgeous, and more self-deprecating in concert); and the stunning "Alexandra Leaving." As he had done with Lorca's "Little Viennese Waltz" back on I'm Your Man, Cohen had taken a poem by a modern European master, and transformed it into a song for his own purposes. While his translation of Lorca's words had been exceptionally free, it very much maintained the spirit and themes of Lorca's poem. By comparison, Cohen's treatment of C.P. Cavafy's "The God Abandons Antony" is remarkably faithful to the original, save for one small detail. While Cavafy's poem is about the pain and despair of the defeated Mark Antony, as he prepares to leave Alexandria forever - for the great city, Cohen substitutes a woman named Alexandra. Which answers to its own logic - to Leonard Cohen, losing a woman forever would be every bit as weighty a matter as losing the entire world. Weightier, in fact. Like the poem, much of the song is made up of instructions - how to behave, how to cope with this incredible calamity, this ultimate defeat. How to get on with it.

1. I'm Your Man (February 1988)

This is where everything came together - a new approach to his music, a new voice with which to sing his songs, and a truly astounding batch of new songs. His voice has finished its descent down the scale, he's no longer even pretending to be a humble little folksinger with a guitar. He took these songs on the road, stood in front of a band, and came about as close to swaggering as this instinctively modest man could come. (If you'd written these songs, you would definitely swagger.) As we often see, the worse things seemed to get in the world around him, the more savage and the more cheerfully cynical Cohen could be in response - so he begins with his famous manual for conquest "First We Take Manhattan", celebrating his liberation after his serving his sentence of twenty years of boredom, set to something like a Europop beat made of synthesizers and drum machines. He follows with his sweeping lament for the age of AIDS "Ain't No Cure For Love," the high cynicism of "Everybody Knows," and the hilarious macho posturing of "I'm Your Man." Which brings us to Lorca. Cohen had spoken, with considerable passion, of how his early encounter with the poetry of Federico Garcia Lorca had quite literally changed his life. He would name his daughter after the martyred Spaniard. Here, he takes Lorca's "Little Viennese Waltzes" and surpasses his master. For the rest of his life, every performance he gave would conclude with "Take This Waltz."

Sometimes I think we expect a great artist to be great all the time. It's impossible, of course. Yeats wrote hundreds of poems - they're not all as dazzling as "Easter 1916" or "Among School Children" or "The Second Coming." Bob Dylan's written hundreds of songs - they're not all "Tangled Up in Blue" or "Visions of Johanna" or "It's Alright, Ma." This is every bit as true of Cohen - but while he was indeed, as he himself realized, a minor poet ("but I still love the minor poets!")- he was truly one of the greatest songwriters we will ever get to hear. His best songs will dazzle and astonish us as long as we have ears to hear. Cohen insisted that it wasn't false modesty that made him place Hank Williams a hundred floors above him in the Tower of Song - "I know where Hank Williams stands in the history of popular song" he explained. But he was wrong about that.

He need not look up at anyone.

it wasn't much

I couldn't feel,

so I learned to touch

I've told the truth,

I didn't come all this way to fool you

And even though

It all went wrong

I'll stand before the Lord of Song

With nothing on my tongue