Since the Beatles officially disbanded in April 1970 (Lennon had already quit seven months earlier) the four ex-Beatles have issued 62 solo albums. I'm not going to look at all of them, mainly because 20 of them are by Ringo Starr. Ringo remains a great drummer and and an engaging live performer, but while he's managed to make a couple of excellent singles along the way, he has never made a good album. Not even once. (1973's Ringo! may have been a smash success that generated three hit singles, and it is indeed better than the very worst efforts of each of his bandmates, but it's still not a good record.) That still leaves 42 albums, and the problem with considering them collectively is that more than half of them are Paul McCartney's work. This is mostly because John Lennon and George Harrison both died young, but it's also because McCartney has never stopped working. Lennon and Harrison each took extended breaks from music in the midst of their solo careers, and both men put out exactly one record after turning 40 - Lennon because he was murdered, Harrison because he walked away from music and pursued his other interests: movie production, auto racing, meditation, tending his garden.

Prologue: The Three Boys

These three men - Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison - came together when they were very, very young and those original dynamics would linger through their lifetimes. Lennon was the oldest, by what was a considerable degree for teenagers - he was almost 17 when he met a 15 year old McCartney. Lennon liked to be the leader of his little gang of friends, who all tended to be a year or two younger than he was. He immediately recognized a formidable talent in McCartney and he also recognized that it would be a struggle to keep him in line.

Harrison was McCartney's friend. They used to share a long bus ride to school at the Liverpool Institute. When McCartney flubbed his big guitar solo at his first gig, Lennon started thinking they needed a better guitar player. George was still just 14 years old - he was even younger than Paul, and he was still very small. Lennon wasn't sure about taking on this little kid, but he famously passed his audition on top of the bus and then there were three.

But Lennon was always the oldest boy, always the leader, always the star. McCartney and Harrison idolized him. "He was our little Elvis," McCartney would remember. "I always looked up to you" Harrison would sing. In time this would change the dynamic between Harrison and McCartney. Harrison would eventually come to deeply resent his secondary position within the band, but he would focus all of that resentment on McCartney. John Lennon could really do no wrong in his eyes. (Never mind that it was Lennon who would get into the habit of absenting himself from the studio when it was time to work on one of George's songs.) Harrison spent the last 30 years of his life slagging off McCartney in the press at regular intervals, saying things like "I'd rather have Willie Weeks playing bass than Paul McCartney." This is an insane proposition on the face of it, but Willie Weeks was an employee playing what George wanted him to play. Interestingly, McCartney never once took any notice of this sort of thing. John Lennon could get under McCartney's skin, and provoke a response. George never could.

There was one crucial difference between the three boys. Lennon and McCartney were both instinctively, naturally creative. Both boys liked to write stories and poems, both boys liked to draw. For Lennon, an only child, a reader in a house full of books, these became an outlet for self-expression. For McCartney, it was simply something that came naturally, something that he enjoyed doing. Both boys had tried their hand at writing a song before they'd even met. Harrison was different. He was very much a little rebel, but he wasn't a creative boy. He was a student, obsessed with guitars. He didn't have, and never would have, McCartney's natural command of the instrument. Instead he worked and worked and studied and studied. But writing did not come naturally to him, as it did to Lennon and McCartney. Harrison was 20 years old when he wrote his first song, for the Beatles' second album, and that was largely as an exercise to discover if he could actually do it.

A Digression on Bob Dylan and the Beatles

It never occurred to any of these three songwriters that the lyrics of the pop music they played could have any significance whatsoever until they came across Bob Dylan's work. Dylan and the Beatles would have an enormous impact on one another, albeit in at least four different ways. Dylan was affected by the Beatles as a collective. The songwriting on Blonde on Blonde, in particular, is impossible to imagine without their influence. Whereas each of the Beatles was affected by Dylan in ways specific to each individual.

Dylan's relationship with Lennon was always a bit competitive. Lennon was possibly a bit jealous that Dylan was the one who quite casually dropped literate lyrics into popular music. It should have been Lennon who thought of that! Lennon, of course, was one of the most conventionally well-read popular musicians ever, even more than Dylan. And over the next few years - beginning, I would say, with "I'm a Loser" on their next album - Lennon's song lyrics became more and more important to him. They became a necessity in his music, his new outlet for what he was thinking and feeling. So Dylan had that on him. But Lennon also intimidated Dylan, which is very, very hard to do. Partially through the power of personality - Dylan is an alpha dog, but so was Lennon - and Lennon, almost effortlessly, was generally the biggest alpha dog on whatever block he was on. But Lennon's sheer talent was also intimidating, in ways that were uncomfortably specific to what Dylan did himself. Dylan would write these lengthy winding epics to tell some story - and Lennon would somehow achieve something of equivalent depth and power with a brevity and concision that's still stunning, in songs like "Girl" and "Norwegian Wood" and "Nowhere Man." They liked one another, but they also made each other slightly uncomfortable, and each was slightly paranoid about the other. ("Was that song a dig at me?").

McCartney's an alpha dog as well, but McCartney's only competitive when he feels like it. He simply feels no need. McCartney's self-confidence is so unshakeable that his default position is that no one can really compete with him anyway. Dylan has confessed to being in awe of McCartney's gifts as a player and composer. But their actual impact on one another has been fairly incidental. As a musician McCartney's first and foremost a melodist and a performer, something Dylan had no impact on at all. And for McCartney, an intelligent sophisticated lyric simply became one more option, something else you could do with a song. They were something that broadened his palette, but they were never required. They were never an actual necessity to the making of a good song. McCartney admires Dylan enormously, of course. He probably admires Brian Wilson even more, though. McCartney admires lots of guys. The two men have never really had a relationship, just a number of friendly encounters.

Dylan was George's discovery and we can all get a little proprietary about our discoveries. He had picked up an import copy of Freewheelin' in Paris, in January 1964, played it for his bandmates, and it blew them all away. (It's what they were listening to while they were writing the Hard Day's Night songs.) George came to think of himself as an alpha dog too, which was why being in the Beatles eventually made him crazy. He could never be an alpha dog in that band, where he would always be Paul's little friend who knew all the guitar chords. George was the Beatle who became Dylan's best friend, and George adopted Dylan the way he adopted one of his Indian gurus - as a great master, whose words are to be quoted as immortal wisdom. George was happy and willing to look up to Dylan, and Dylan is quite comfortable with people who look up to him. It's what he's long been accustomed to.

The Three Solo Careers

On 20 September 1969 John Lennon informed his bandmates that he was leaving the group. Allen Klein urged him to keep this bit of news to himself, as Klein was attempting to negotiate new royalty rates with Capitol and EMI. So Lennon said nothing publicly but before the month was over he had recorded a new single - "Cold Turkey" - the writing of which was credited to Lennon alone, the famous Lennon-McCartney byline apparently a thing of the past. Harrison and McCartney both sat for interviews to promote Abbey Road, but McCartney soon dropped out of sight. Devastated by the band's breakup, he'd fled to his farm in Scotland and begun drinking heavily. A bizarre rumour that he was dead actually began spreading, to the extent that Life magazine actually dispatched a team to Scotland in November to find him. While assuring the world that the rumours of his death were greatly exaggerated, McCartney let slip that "the Beatles thing is over." Amazingly, no one picked up on it.

In January 1970, McCartney returned to London and with the two remaining Beatles spent a day recording Harrison's "I Me Mine" which was needed for the Let It Be album. He then began recording new songs, by himself in his Cavendish Avenue home, on a Studer 4 track machine. Later that month, Lennon woke up, wrote a song, and wanted to record it that very day. He rounded up some friends and Harrison suggested they bring in the legendary Phil Spector to produce. Spector happened to be in town, a guest of Allen Klein. They caught Spector on a good day and he understood exactly what Lennon wanted. Lennon had asked for a 1950s sound on "Instant Karma," something right in Spector's wheelhouse.

In February McCartney moved his sessions into Abbey Road - under an assumed name so that no one else would know what he up to - to finish recording and mixing his first album.

In March Lennon and Harrison asked Spector to see what he could make of the abandoned recordings made twelve months earlier for the Get Back project. Within a week, Spector had whipped together a new version of the abandoned record, one that could be released in conjunction with the Let It Be film. Lennon and Harrison were both pleased that Spector had salvaged something - anything - out of the Get Back tapes, but when McCartney finally got around to listening to it he was horrified at Spector's work on his songs. He demanded changes. Unluckily for him, it was too late. The others wanted the album to come out at the same time as the film. They also decided they couldn't have McCartney's album come out at the same time as the film. They informed McCartney, by a letter that Ringo offered to deliver in person, that his album would have to wait until June. McCartney hit the roof. He wasn't willing to wait a single day for the convenience of a band that as far as he could tell no longer even existed. And so his first solo album was released in early April.

McCartney had included a press release along with his album that was immediately interpreted as his declaration that he'd left the band. That wasn't quite what he'd said, but it was certainly how the world - and his bandmates - took it. The breakup became global news, and McCartney would forever take the heat for ending the band. The dream was over. Harrison's first proper solo album would arrive in late November, Lennon's two weeks after that.

The three men had gradually evolved different ways of working. This had begun while the band was still active, once they were afforded unlimited studio time to do whatever they liked. I have no doubt that this contributed to the increasing strains between them.

Lennon, of course, was famously impatient and famously challenged by technology in all its forms - from tape recorders to motor cars. The memoirs of George Martin and Geoff Emerick provide plenty of amusing anecdotes to illustrate. But these mostly relate to Lennon's rather brief excursion into experimental sounds in 1966-67 - "Tomorrow Never Knows," "Strawberry Fields," "I Am the Walrus." In the studio, Lennon generally knew exactly what he wanted and, more to the point, exactly how to get it. (Whatever its shortcomings, Rock'n'Roll demonstrates that Lennon certainly didn't need Phil Spector to recreate the Wall of Sound.) Most of Lennon's solo records were cut with professional session pros who could figure out what he wanted and provide it, quickly.

At the other extreme, George Harrison liked to play his songs over and over and over and let the arrangements emerge, organically. This was fine with McCartney to a point - if he could tell that a take wasn't working, he could start experimenting, seeing what might work for the next take. But it mostly just drove Lennon crazy, and he eventually simply stopped showing up to work on Harrison's songs much of the time. Most of Harrison's records would be made with a regular cast of his old friends, usually at his home studio at Friar Park (the two records he made in American studios with session players are the absolute nadir of his solo career) - time and money were not an issue, everyone was comfortable, just sitting around playing.

Finally, while McCartney wrote songs, he also wrote records - he often went into the studio with a fully thought out concept of how the final record should sound. He would then drive his bandmates mad chasing after it, especially when they didn't care much for the song in the first place. McCartney worked with session pros even less often than Harrison - Ram is really the one exception, and the drummer on that record soon joined Wings anyway. McCartney plays everything a rock band needs. He actually has a distinctive style as a bassist, a guitarist, a keyboard player, and a drummer. While he has formed at least three good bands in his solo career - he can't do everything on stage, and he loves to perform - and he has used his bands on some of his albums, he has regularly found that the most reliable way to get the results he wants is to do most of the work himself.

Almost all of the Beatles recordings were made at EMI's studios on Abbey Road. Lennon and Harrison made their first solo albums there as well, and it's where McCartney finished up his first album - but after that, they mostly moved on. Lennon made one record at his home in Ascot, then moved to America and used the big studios there, usually the Record Plant in New York. Harrison made almost all of his subsequent recordings at his home studio at Friar Park, with the exception of the two albums he made in Los Angeles. While both dabbled in avant-garde recordings early in their solo careers, both men were on some level fundamentally conservative, always preferring the music of their youth to that of their contemporaries (never mind those who came after), always preferring to work with familiar faces in familiar surroundings. McCartney is the one who has always been the adventurer, the one with unlimited musical curiosity. While he would return to Abbey Road from time to time, he would also work in at least half a dozen other London studios as well as at his own home studios in London, Scotland, and Sussex. And he would venture abroad as well, recording in New York, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Nashville, Nigeria, and Montserrat. He has regularly dabbled in outside projects that have nothing to do with the kind of music that made him famous, from traditional classical pieces to experiments in noise and electronica. On his recent albums, he has brought in producers half his age to collaborate with, people who made their reputations with contemporary acts ranging from Radiohead to Adele to OneRepublic - while he accepts that a man in his 70s has no place at the top of today's pop charts, he has remained eternally curious about what goes on there and how he can still have some fun of his own with it.

British artists who came up in the 1960s always regarded albums and singles as things that were separate from one another. This practice changed for the most part in the 1970s, with singles taken from albums (and often seen as a way to promote the album they came from.) Even so, Lennon and (especially) McCartney still issued standalone singles from time to time, and they do represent some of their very best solo work. Harrison took almost all of his singles from his albums, although like many other artists he often used the B-sides to find homes for songs that hadn't ended up on an album. McCartney did likewise; Lennon generally gave the B-side to Yoko. Oddly enough perhaps, their solo work usually fared better on the US charts than in the UK. McCartney scored nine US number ones, just three in the UK; George had three US number ones, John and Ringo both had two; John had three UK number ones, George just one, and Ringo's been shut out.

GEORGE HARRISON

Robert Christgau once described Harrison as " a borderline hitter they can pitch around after the sluggers are traded away." It's an odd way to put it, but he's on to something. Harrison is certainly an acceptable vocalist (his falsetto is especially appealing) - but he was in the same band as two of the greatest rock singers who ever lived. Compared to Lennon and McCartney, Harrison's voice is somewhat thin, lacking in both range and power; more importantly he was generally incapable of the variety of different vocal approaches both of his bandmates could manage. He carried his share of the vocal load on stage and he was always a very fine harmony singer, but he generally only sang one or two tracks on the band's first few albums. As he wasn't yet writing seriously, these would either be covers or numbers Lennon had written for him.

Harrison got his first composition on the band's second album. He placed two more of his songs on both Help! and Rubber Soul but his real breakthrough as a songwriter came with Revolver - the band's seventh album - where he came up with two of the better tracks with "Taxman" and "I Want to Tell You." That same album, however, also saw his first excursion into attempting to compose Indian music in a Western context, and this quixotic pursuit would dominate his musical path for the next couple of years. He didn't really return to writing Western music until the White Album, but when he did, he did so with an abundance that was a completely new development. By the time the band dissolved, he had a large backlog of unrecorded songs. But this was an atypical moment. Harrison always had trouble writing lyrics. His very difficulty in finding ways to express himself verbally would itself be a recurring theme in his writing. He was never prolific - or more accurately, he was never someone who produced good songs in abundance. For him to come up with ten good songs would usually be the work of at least five years. He released eight albums in his first twelve years as a solo artist, when in truth he probably had enough good songs for three. Contemporary artists may work on that sort of schedule - one album every four or five years - but expectations were very different when Harrison was active. And so he cranked out all these songs during his solo years. So many of them are so utterly forgettable that it's all too easy to miss the good ones along the way.

Harrison always seemed to believe that a song needed to say something important. It should express something important to the writer, or it should say something important about the world or about life. He often seemed to disapprove of music that was just fun, even his own. He actually seemed apologetic about his songs if they were just catchy pop tunes. (He would eventually seem to lighten up considerably as he got older.) But in 1970, the world most certainly wanted and expected Big Statements from a Beatle, and Harrison was the man who met that demand. McCartney's record was a humble, homemade thing. Lennon's record was intensely personal. Harrison spoke to the world, and the world was happy to hear from him. It was mostly downhill from there, of course, but there were many good moments along the way.

10. Dark Horse (Dec. 1974)

John Lennon's Lost Weekend has gone down in rock'n'roll lore - George Harrison's not so much. But it was every bit as real, and shared many of the same features - a marriage disintegrating, a lot of substance abuse.. By mid 1974, Harrison had temporarily relocated to Los Angeles. He was in terrible physical shape, drinking too much and doing much too much cocaine. His wife had finally left him, for his best friend - Harrison had then had a brief affair with Ringo's wife Maureen, which shocked and horrified all his ex-bandmates. In these bizarre circumstances, Harrison had planned to do a 45 date tour of North America. He would be the first former Beatle to tour in the US, and he had an album he wanted to finish up first. The sessions for the album took place while he rehearsed his band for the upcoming tour. His voice, which was already in bad shape when work on the album began, was completely shot by the end of the sessions. He had little in the way of new material. His first two solo albums had exhausted his backlog as well as everything he'd written since. The completed record has just nine tracks - it's padded out with a pointless instrumental jam, an Everly Brothers cover, and a song he'd already given to Ronnie Wood for Wood's first solo album. That song, "Far East Man," is the best thing on this record but it's heard to better advantage on Wood's album. It's remarkable that Harrison even went ahead with the album release and the tour. These are the worst vocal performances any Beatle ever put his name on, including everything Ringo ever did. It's very close to being unlistenable.

9. Extra Texture (Sep. 1975)

Harrison's Lost Weekend in the U.S. continued on into 1975. On this record, we can hear that his voice has recovered but he doesn't have a single melody worth singing. He doesn't have even one good song. Not a one. He doesn't even have a lot of ideas - one of the songs is called "This Guitar Can't Keep From Crying" and as sequels go... it ain't Godfather II. The only good thing that came out of this whole period was Harrison meeting and marrying Olivia Arias.

8. Gone Troppo (Nov. 1982)

While he'd had something of a hit in North America with his previous album and its single, neither had made much impact in England, where Harrison actually lived (most of the time, anyway - he'd bought his property in Hawaii by then.) He felt alienated from the music business in general and was far more interested in movie production and Formula 1 racing. Harrison declined to lift a finger to promote this album, chose not to make any videos for its two singles, and generally left his record company at a complete loss as to how to market the thing. So they didn't bother, and it sank like a stone. At this remove, one wonders why he even bothered with the record. He certainly didn't seem to care very much. He had enough good material for about half an album; the rest is padded out with a cover and an instrumental. The closing track was originally presented to the Beatles on the famous Esher demos in 1968, but it was never attempted by them. Besides the four or five halfway decent songs, the most interesting thing about the music to me is the influence of Hawaiian music on his slide playing, which is all over the record. Which is nice if you're a fan of that sort of thing. Too much of it starts to cloy after a while.

7. Thirty-Three & 1/3 (Nov. 1976)

In its moment, this was presented (and perceived) as a comeback. Harrison had finally pulled himself together. A bout of hepatitis had probably got his attention. He cleaned up his act, he got out of L.A., with its studios and session men, and he left all its temptations behind him. Finally free from Apple, Harrison had signed with Warner Brothers and seemed to be trying much, much harder. He even came up with a couple of pretty good songs - "Crackerbox Palace" and "This Song," about his troubles with copyright law. He worked in his home studio with a bunch of old chums. It's well recorded and well played, and he's starting to sound like himself again. Unfortunately, most of the songs simply don't amount to much. It's mostly filler, though it passes by painlessly enough.

6. Somewhere in England (Jun. 1981)

Executives at Warner Brothers gave Harrison a dose of reality therapy when he submitted his original version of this album in September 1980. They rejected it. They even vetoed his choice for a cover. Harrison accepted this, however grudgingly, and went back to work. First he recorded a couple of tracks with Ringo, for Starr's next solo album. And Ringo rejected one of them. He didn't like the lyric and he complained that it was pitched too high for his voice anyway. That track was a catchy little shuffle called "All Those Years Ago." After Lennon's murder, Harrison retrofitted the song with new words about his lost bandmate. This made for a very weird track - Harrison's deeply heartfelt reminiscences of his old friend grafted on top of this bouncy tune. (The contrast with McCartney's haunted, lost "Here Today" is startling.) Harrison then added three more new songs while deleting four of the original tracks. I don't really know what Warners problem was - the new tracks definitely didn't make the record any better. I think Harrison's original version is a little stronger than what was actually released. The revised version did provide him with an unexpected hit single, although I have never had any use for "All These Years Ago" myself. One of the other new tracks ("Blood From a Clone") is an angry screed at the executives who had the unmitigated gall to send a Beatle back into the shop. That's amusing, and I'm sure it was satisfying for the artist but it's still one of the weakest things on the album. And yet, this is a better record than I remember it being. It's a little telling, though, that what might be the two best songs on it were written by Hoagy Carmichael.

5. Living in the Material World (May 1973)

Between All Things Must Pass and this album, Harrison had organized The Concert for Bangladesh, with its accompanying film and album, an enterprise that took a great deal of his time and energy. He issued the decent standalone single "Bangla Desh" in support of the cause (the charming flip side, "Deep Blue", is a forgotten gem.) This frustrating album has some of the finest melodies Harrison ever devised and some of the most banal lyrics. ("the leaders of nations, they're acting like big girls.") This is where Harrison cemented his image as the most preachy and annoying artist in the world - far too often these songs lecture and heckle everyone who hasn't seen the same light that he has. It's frustrating because there is so much that is appealing about the record. For one thing, it simply sounds absolutely wonderful. Some of the tracks on All Things Must Pass had featured no less than six acoustic guitar players strumming away. They're all gone - it's just George on this record. His voice is up front, not swallowed by oceans of reverb, and he's singing as well as he ever did. Some of the ballads are quite beautiful. And the glorious "Don't Let Me Wait Too Long" should have been a single, and it should have gone to number one. It's irresistible. (As it happened, "Give Me Love" was the single, and it went to number one; its flip side, "Miss O'Dell" is a forgotten delight, although Harrison keeps cracking up while singing it.) But the fast songs - the title track in particular - are not all that good, although I do rather like the stop and start rhythms of the vastly pissed-off "Sue Me, Sue You Blues." And as pretty as the ballads are, you still keep hearing this fabulously rich, fabulously self-satisfied pop star telling you how you should be living your life.

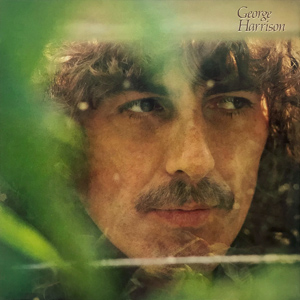

4. George Harrison (Feb. 1979)

Harrison's better records all have two things in common: a significant interval since his previous record (to give him enough time to come up with better songs) and a third-party - in this case, Russ Titleman - handling the production (as left to his own devices Harrison often tended to bury his own voice in messy and overproduced mixes.) "Not Guilty," of course, was one of the Esher demos - the Beatles did more than 100 takes of it the sessions for the White Album without getting a usable version. Harrison hadn't yet figured out how to sing it back in 1968 - here, he slows it down slightly and drops all the electric guitars and gets the track to work. It's followed by one of his sequel songs - this one, "Here Comes the Moon," is the weakest track on the record. Harrison was a newly married man and these songs seem to be written in the first blush of his new love - he seems to be thinking about Olivia more than Krishna. The record hasn't aged all that well - I liked it much better in its moment. Now it sounds just a little too soft, a little too much like yacht rock. But the highlights are well worth your acquaintance, especially "If You Believe," and the wonderful "Blow Away."

3. Cloud Nine (Nov. 1987)

Dave Edmunds, Harrison's friend and neighbour, helped hook him up with Jeff Lynne of ELO for what truly would turn out to be a comeback effort. (This would lead, soon enough, to the Traveling Wilburys and a number of fine related projects. Dylan got involved because he was Harrison's friend, Tom Petty because he was Dylan's friend, Roy Orbison because he went way back with Harrison and everyone just admired him anyway. The world ended up with the Wilburys record, Orbison's brief but glorious comeback, Petty's Full Moon Fever. Much of this simply because Dave Edmunds lived in Henley.) On Harrison's own record, one of the smart things Lynne did was simply place the voice higher in the mix. Harrison had gradually gotten into the habit of burying his voice deeper in the mix of tracks that had also grown more and more cluttered over the years. Lynne brought up the vocals and helped to streamline the arrangements. Harrison's guitars dominate the record, for once. The album opens with the title track, a modest number notable mainly for Harrison and Eric Clapton trading off guitar parts. The second track features more of the same, except it's a better song, and "Fish on the Sand" which follows is even better. "Just For Today" is one of the best ballads he ever did, and "When We Was Fab" is a hoot. These are not particularly ambitious songs, which from Harrison is a welcome change. All too often, he had proceeded as if it was his solemn duty to tell the world things it needed to know. Here, he's just playing some solid tunes. He even became the last (to date!) former Beatle to hit the top of the charts with his remake of James Ray's "Got My Mind Set on You" an oldie that absolutely no one else would have known (it had failed to even chart upon its release in 1962.) I think it's a pretty lame song, the weakest track on the record, and I don't know what George ever heard in it. It doesn't even seem to fit with the rest of the album, which is probably why it gets placed at the end. But Harrison clearly loves it anyway and performs it with spirit and enthusiasm.

2. Brainwashed (Nov. 2002)

Harrison worked on this casually, in his spare time, for more than a decade. But in 2001, he became seriously ill and finishing this last project took on a degree of urgency. When Harrison realized he wasn't going to live long enough to see it through, he left detailed instructions with his son Dhani and his old collaborator Jeff Lynne on how he wanted the record to be finished. After taking a few months to grieve, they got to work and they did the artist proud. The opening "Any Road" is one of the finest songs of a career that was already not without accomplishment. (The weakest track is probably the one he'd already farmed out to Clapton fifteen years before, "Run So Far.") The record closes, appropriately for this artist, with a brisk denunciation of the things of this world - but here he makes it work, and he closes his career quietly murmuring what one assumes are Hindu scriptures over understated organ and tabla. It's remarkably moving. The whole thing is as strong a collection of songs as Harrison ever assembled - well, he did take more than ten years to write these songs - and this is as lively and vigorous as he ever sounded in his solo career. A magnificent testament.

1. All Things Must Pass (Nov. 1970)

There are two main problems with Harrison's first solo album. The first problem is the sheer excess of the whole package. Three records? Seriously? Okay, no one's ever played the third record of pointless studio jams more than once or twice. But even two records was pushing the envelope for this artist, his writing and his voice. The bigger problem is Phil Spector. Here's the thing about Phil Spector. He made his reputation in the early 1960s by making records that sounded enormous and overwhelming on the crappy radios and record players of the day. By 1970, most music fans had far better systems available in their own homes and the far better signal on FM radio to listen to. No one needed Spector's magic to get something that sounded impressive. And Spector's techniques were easy enough to master anyway - Brian Wilson had them all figured out by 1966. Spector wasn't much involved in the actual sessions for Harrison's record - when he was actually present at Abbey Road he spent most of his time drinking brandy. But Harrison adopted Spector's approach - layers of acoustic guitars, multiple drummers and bass players - and Spector did take charge of the mixing, in which he smothered every track with oceans of reverb. The sound hasn't worn very well - Harrison himself would shudder at it thirty years later. But there's a really, really good twelve song single album buried in here. (I think you have to drop the second version of "Isn't It a Pity", the two Dylan numbers, and two others of your choice.) With "My Sweet Lord" Harrison became the first ex-Beatle to score his own number own single, in both the US and the UK; he also landed himself years of legal troubles as the song's obvious resemblance to "He's So Fine" immediately prompted lawsuits over copyright infringement. (I can't believe that no one would have pointed this out to Harrison at the time. He must have figured he'd simply get away with it, being a Beatle and all.) That said, George's song is by far the better of the two. One of the odd things about the album is that Harrison is essentially working with two different bands on this record. Roughly half the album, in particular the up-tempo, soul-influenced stomps like "What Is Life" and "Awaiting On You All," uses Eric Clapton and the players Harrison had met while touring briefly with Delaney & Bonnie at the end of 1969 - Jim Gordon, Carl Radle, Bobby Whitlock. (Those three and Clapton would soon turn into Derek & the Dominos.) The rest of the tracks rely on his old friends Klaus Voorman, Billy Preston, and Ringo Starr. This might have made for a somewhat schizophrenic listening experience if the whole thing hadn't all been smothered in Spector's endless reverb. But the album rocks harder and has more good songs than any other album in his career. It's a real shame he didn't live long enough to remix it, as he had hoped to do one day.

PAUL McCARTNEY

"I'm in awe of McCartney. He's about the only one that I am in awe of, but I'm in awe of him. He can do it all and he's never let up. He's got the gift for melody, he's got the rhythm, he can play any instrument. He can scream and shout as good as anybody and he can sing a ballad as good as anybody. And his melodies are, you know, effortless!" (Bob Dylan in 2007)

Well, yeah. Consider one day in June 1965. Over the course of a few hours, McCartney recorded, in succession, three of his compositions: "I'm Down," "Yesterday," and "I've Just Seen a Face. Just one after another - as wild and feral a rocker as anyone has ever sung, the traditional pop standard to top all pop standards, and a new kind of music quite unlike anything being done by anyone else at the time. This really happened. Epic poetry has been written about far less impressive accomplishments. And a few days later he marked his 23rd birthday.

There's a generosity of spirit in much of McCartney's music that's one of his most attractive qualities. He's never been all that interested in using songs as a vehicle for self-expression and he's always been willing to write about the lives of other people - sometimes real people, sometimes just people he imagines. Harrison and Lennon both expressed in their music a great deal of concern for the state of the world and the fate of humankind but they seldom seemed enormously interested in any of the people living in it. But from Father McKenzie to Desmond and Molly, from his working girl in "Another Day" to his own Uncle Albert - McCartney thinks about these people, cares about them, tries to imagine them living their lives.

McCartney isn't merely a natural entertainer - he's an incorrigible ham and always has been. He's never been able to help it. (It's what always made him, by far, the worst screen actor of the four Beatles. Ringo was obviously the best - try to find That'll Be The Day if you don't believe me - but if George had only been interested he might have been as good!) There's something about McCartney's relentless optimism that can almost be grating at times. It's as if nothing ever fazes him, as if nothing even can, as if there's nothing that a silly love song can't fix. The world isn't like that for most of us. But very few people have done less to screw up their own good fortune than Paul McCartney.

There was a moment - it came between the day in September 1969 when Lennon told his bandmates that he was quitting the Beatles and the following January when McCartney came back to London -when Paul McCartney wasn't sure about his future, or if he even had one. His band was dissolving in acrimony, his best friend and lifelong musical partner had turned on him. For a moment there, he lost himself as another famous British band would sing one day. But the moment passed, and he went back to work.

McCartney has been a working musician all his life. His gift for melody is one of the great and inexplicable wonders of the world - it seems to come to him as naturally a leaves come to a tree, so naturally that it has far too often made him downright lazy as a songwriter. This was especially true during Linda's lifetime, while they were raising their brood of children. McCartney never stopped being a working musician, but his output has always been notoriously erratic, and the quality of his work varies wildly - not just from album to another, but from one song to the next on the same album. He has actually been a far more consistent and reliable artist during these past twenty years, as he moved into middle and old age. The man's resources, it appears, are inexhaustible.

It can't possibly be as easy as he makes it look. It just can't. But making it look easy is what he does. It's what he's always done.

24 Red Rose Speedway (Apr. 1973)

It's remarkable that an artist with McCartney's matchless gift for melody could have coughed up such crap. Even more remarkable, he actually scored a number one hit with the egregious "My Love," as lousy a ballad as he ever wrote in his life. There's one vaguely decent melody - "Big Barn Bed" - which, true to form, he joins with lyrics that are nonsense gobbledygook. Weeping armadillo, yes? No. Between Wild Life and this, McCartney had issued three standalone singles: he'd responded to Bloody Sunday by instantly writing "Give Ireland Back to the Irish" which was somewhat confused and incoherent but definitely had its heart in the right place. It was banned by the BBC. He'd followed that up, though, with "Mary Had a Little Lamb," which was both an attempt to write a genuine song for children while taking an oblique and ironic swing at his critics (and his censors.) He managed to get banned again with his next single, the stomping rocker "Hi Hi Hi" which was either about drugs or a little too sexually explicit. None of the singles were particularly great, but all were much better than anything on the album. The cover is by far the best thing about the record.

23. Wild Life (Dec. 1971)

This was the first Wings album, bashed out in a single week in the summer of 1971, and for some reason McCartney couldn't be bothered to write any real songs for the occasion. The only interesting track is "Dear Friend," a weary and somewhat pained response to "How Do You Sleep." McCartney actually has very little to say to his old friend, which seems odd, but what can you really say to something like that anyway?

22. Kisses on the Bottom (Feb. 2012)

A collection of old jazz and pop standards? What for? McCartney is certainly more than capable of singing these kind of songs. He's done it before, going right back to "A Taste of Honey" on the first Beatles album. There just doesn't seem to be much point. When Ringo began his solo career with a similar project back in 1970, he explained that he'd done it for his mum. McCartney would have heard lots of this music from his father, an amateur musician himself, but Jim McCartney was long gone by 2012. It's my view that the Great American Songbook is now a dead end. Frank Sinatra defined it so thoroughly that there's simply nothing anyone can do with it now. Anyone's rendition of one of these songs will always invite comparison with what Sinatra did with it, and Frank will win that argument every single time. Bob Dylan tried his best, and so does McCartney, but they're both beating a dead horse. McCartney's usually not the kind of singer who redefines the songs he covers anyway.

21. Pipes of Peace (Oct. 1983)

This was apparently conceived as the companion to Tug of War and George Martin was still around to handle the production. It doesn't work nearly as well this time, mostly because all the good songs had been used on the first record. Here we get that record's leftovers, and a bit of McCartney just messing around with stuff. He still got a number one hit out of it, with "Say Say Say," one of two Michael Jackson collaborations. It's easily the most memorable track on the album - the two actually make a pretty decent team. The rest of the songs are so slight that they almost float away, although I promise that the graceful little melody of "So Bad" will stick with you for the rest of your life.

20. Off the Ground (Feb. 1993)

Naturally, McCartney followed his best record in almost a decade (and a hugely successful world tour) with a disappointing piece of work. This shouldn't even be surprising by now. Sometimes it's because he's always been willing to share everything he takes a stab at trying, just to see if it appeals to anyone; sometimes it's as if he's simply not a very good judge of his own work. Because he is such a talented singer and musician, he can always make whatever he's doing sound pretty good, whether there's anything going on or not. But he's not trying anything new here, he's not experimenting - with the possible exception of the tossed-off rocker "Get Out of My Way," the sort of thing he can do in his sleep, McCartney just doesn't have much in the way of interesting songs. Elvis Costello insists that there's a take of "The Lovers That Never Were" in the vault with the greatest vocal performance he's ever heard in his life. It's not the one on the album. McCartney's next couple of years would largely be filled by his participation in the Beatles Anthology project.

19. McCartney II (May 1980)

McCartney created this music in the summer of 1979, just messing around at home by himself. After his famous drug bust in January 1980, he put a halt to all Wings activity and decided to issue this music in the meantime. It shows that he'd gotten better at being a one-man band, but he didn't have any songs as good as "Every Night" lying around (never mind "Maybe I'm Amazed.") He did get yet another number one out of "Coming Up," although it was the live version of the song on the B side that Columbia was actually promoting (for some reason, this number apparently impressed John Lennon enough to stir up a few competitive juices.) The album is a collection of more or less interesting experiments, a great musician just screwing around, trying to learn how to operate these synthesizers. It's since been put forward as a precursor of the low-fi and bedroom pop movements that would emerge in later years, which might be pressing the point a little. But this man's failed experiments and detours into dead ends often find some way to make themselves useful to someone.

18. Back to the Egg (Jun. 1979)

McCartney assembled yet another version of Wings - this was more or less the third band lineup - and he took them into the studio with a batch of songs almost as weak as the ones on Red Rose Speedway. The album had been preceded by the standalone single "Goodnight Tonight", which didn't really amount to much although it was catchy enough to make it into the top five. This version of Wings sounds much better than its predecessors, and this mostly guitar based music rocks much harder than McCartney had done in quite some time. Unfortunately, the songs simply refuse to come to any life of their own. Everything gets thrown at the wall but nothing here sticks, not even a little. It's very frustrating. It's one of those records that generally sounds just fine while it's playing - it's full of spirit and energy, and that alone lifts it above some of the others down here at the bottom of the catalogue. But you won't remember anything about it when it's over.

17. McCartney (April 1970)

An extremely humble debut. Five of the tracks are fairly pointless instrumentals. Several of the songs sound half-finished at best. Two others, including the lovely "Junk," were left over from the White Album days. Very humble indeed, and so much more had been expected. But "Every Night" is outstanding, and "Maybe I'm Amazed" is absolutely stunning - a fabulous song, an amazing recording, and one of the world's greatest singers singing as if his very life depended on it. An incredible performance, one that can still make you drop whatever you're doing in awe and wonder.

16. Press to Play (Aug. 1986)

So many of the rock icons of the 1960s had carried on well enough through the following decade only to completely lose the plot in the 1980s - Bob Dylan, Neil Young, the Who and the Kinks. The former Beatles were no exception. McCartney had spent much of his energy in the years prior on his movie musical, Give My Regards to Broad Street. While the soundtrack was a success (it had just three new songs and a bunch of old Beatles numbers), the movie was truly awful and prompted universal derision. So McCartney recruited the hottest young producer in England (Hugh Padgham) and a new songwriting partner (Eric Stewart from 10cc, who he'd been working with since Tug of War.) While the packaging suggests the listener will be in for soft, tuneful McCartney, that's really not what you get. This is a rather adventurous record, with more spunk and energy that McCartney had shown in a long time. It's just that the songs don't stick. In that respect, it resembles nothing so much as Back to the Egg. It didn't help that the lead single ("Press") was a dreadful piece of mid-80s drum machine based synth-pop. It failed to even crack the top 30, and I have to think it helped to sink the album as well.

15. London Town (Mar. 1978)

Yacht rock! The soft, smooth sound of the 1970s! It's seldom associated with McCartney - names like Christopher Cross and Michael McDonald are usually mentioned. I would point out that not only is London Town quite typical of the style - it was mostly recorded on an actual yacht. Wings had planned to keep working through 1977, but Linda's pregnancy cancelled those plans. McCartney dropped a one-off single in the meantime, a tribute to the Scottish countryside he loved so dearly, with bagpipes and everything. Somewhat unexpectedly, "Mull of Kintyre" became not just McCartney's first number one hit in his home country - it became the UK's best-selling single of all time. By the time James McCartney was born, in September, with just three tracks made for the next album, half the band had drifted away - drummer Joe English was homesick for America and guitarist Jimmy McCulloch signed up with the Small Faces. This left the core three of Paul, his wife, and the faithful Denny Laine. This was the trio that had made Band on the Run, but the trick didn't work quite a well a second time. While he'd toured the world to rapturous crowds (I was one of them, 4 June 1976 in St. Paul - yes, that's really where I saw him!) - and he'd hit the Christmas market with a live triple album, it had been two full years since McCartney had released an album of new music, the longest such gap since he became a professional musician. That amount of time should have given him a better batch of songs than it did. He still got another US number one with the single, "With a Little Luck," a track that nicely sums up everything that can drive you mad about McCartney - the song drifts along pleasantly enough, doesn't really do or say much of anything, but that damn melody will stick with you whether you like it or not.

14. Wings at the Speed of Sound (Mar. 1976)

The title describes how it was made - McCartney had already begun his first big world tour with Wings and one suspects he wanted to have some new music in the shops before bringing the show to America. (He certainly didn't put much effort into the album cover, although McCartney has reliably had by far the worst taste in album covers of all the ex-Beatles. George had the best, easily.) McCartney sometimes like to pretend that Wings was a real band rather than merely his own vehicle. It sometimes seemed that the person he was really trying to convince was himself. On this occasion, he actually turned over a track to each of his four bandmates, despite the fact that was ever only one good singer and songwriter in Wings. The most notorious track is "Silly Love Songs," yet another number one record, but a hit which has managed to follow McCartney around ever since (not that he actually worries his pretty head about it too much.) That's all he ever does, his critics say. But no songwriter has ever had a better grasp of the fundamental truth at the heart of every silly love song. Which is that they aren't silly at all. This is still not much of an album. The best track is the raging, surging "Beware My Love," largely because Paul simply sings the living crap out of it.

13. Flowers in the Dirt (Jun. 1989)

In general, the 1980s had not been good to McCartney. It began, of course, with his drugs bust in Japan and John Lennon's murder. After making one excellent album, he'd made a pair of lackluster follow-ups and devoted a lot of time and effort to his awful film project. He didn't have a band, and hadn't toured anywhere since the final Wings trek around the UK in 1979. As always, he rallied. He put together an excellent band, a far better unit than any of the various incarnations of Wings, with ex-Pretender Robbie McIntosh and Hamish Stuart. He decided to try writing with a partner and who could be a better fit than a famously acerbic Scouser - Elvis Costello. It didn't work quite as well as his first such partnership - how could it? - but they did come up with a few good songs, and his first record with an actual band since Back to the Egg was very much a step in the right direction. "My Brave Face" was a minor hit and I've always regarded "Figure of Eight" as one of his best ever solo tracks, a melodic rocker that just won't let go. If nothing else, it sounds like he's actually trying again

12. Venus and Mars (May 1975)

McCartney was fairly quiet for the first half of 1974. He spent the first few months of the year helping his brother Mike make his solo album (the unjustly forgotten McGear) and then rebuilding Wings into a viable band. Jimmy McCulloch and Geoff Britton filled out the lineup and in the summer they went down to Nashville and cut a tremendous single - the stomping rocker "Junior's Farm" and its B side, a friendly country tune called "Sally G." That was it for Britton, who didn't mesh well with the rest of the band. McCartney went looking for another drummer, while also being briefly distracted by the illusory possibility of once more collaborating with John Lennon, which didn't pan out as Yoko decided this was the moment for her and Lennon to reunite. By the time McCartney finally got around to working on his next album, he had a pretty impressive batch of songs to work with. He and his band went down to New Orleans to record them and for one of the few times in his career (at least until we moved into the 21st century) he was able to issue two very decent albums in succession. A graph of Lennon's career would begin at the top and then slowly and inexorably decline; Harrison would similarly begin at the top, quickly plunge to the lowest depths, and then gradually rise up with an impressive rally at the end. But McCartney would be up and down, up and down, up and down, as unreliable as the weather. Venus and Mars functions almost as a tour of all the different kinds of music McCartney can do, from the powerhouse rock of - what else? - "Rock Show" to the music hall of "You Gave Me the Answer" to the comic-book whimsy of "Magneto and Titanium Man." The lead single, "Listen to What the Man Said," was not one of the better tracks but it gave him another American number one anyway.

11. McCartney III (Dec. 2020)

McCartney's most recent release is his third effort made entirely at home all by himself (hence the title) and it's probably the most consistent overall of the three. It doesn't have the dazzling heights of the first one, and of course the voice is no longer quite what it was (but he actually sounds better here than he did on Egypt Station.) There's simply much more to this record than to either of its one-man band predecessors. He does seem to believe these days that each record requires one vulgar throwaway ("Lavatory Lil" on this one), but this is a varied and interesting collection of songs. He's mostly just following his restless late-period muse wherever it might lead, trying out different kinds of things and seeing what he gets. Among other things, he gets what is probably the best instrumental of his career ("Long Tailed Winter Bird"), a strange extended exploration ("Deep Deep Feeling,") and a positively heavy workout ("Slidin',") and a few songs that grow on you just a little more than you expect them to.

10. Driving Rain (Nov. 2001)

After the small pleasures of Flaming Pie and the relentless rock of Run Devil Run, McCartney was feeling ambitious again. He brought in an outside producer (David Kahne) and started to assemble a band - drummer Abe Laboriel and guitarist Rusty Anderson are still part of his touring outfit two decades later - and began to enjoy the idea of just being the bass player in a band. He also decided to try to recreate the work habits of the early Beatles days - working to strict deadlines, learning the songs at the session. The middle-aged widower had fallen in love - it didn't end well, but it's the clear inspiration behind many of these songs. George Harrison was seriously ill in 2001, and McCartney - who also visited India around this time, for the first since 1968 - does seem to have his old bandmate on his mind. The chorus melody of "Tiny Bubble" practically quotes that of "Piggies" (McCartney's song is better) and the instrumental "Riding into Jaipur" actually makes use of Indian drones and percussion and something that sounds vaguely like a sitar (although it isn't.) It probably runs too long - more than an hour - and the concluding jam definitely goes on much too long, even after Kahne trimmed it down to a mere ten minutes. This kind of self-indulgence is practically the point, though - McCartney's stretching himself in ways he hadn't attempted in years and years.

9. Egypt Station (Sep. 2018)

At last, at long last, one can hear McCartney's voice beginning to fray as he moves into his mid 70s. It hurts a little to hear it. No one cares all that much that Bob Dylan's voice has been totally shot for at least twenty years but McCartney's a different case - his voice was so very beautiful, a perfect instrument for anything any song required. He still sounds like himself, but those famous pipes are beginning to thicken and coarsen, just a little. At this point in his career, he obviously has nothing to prove to anyone anymore. He's just amusing himself and hoping you'll be entertained too. He's still adventurous, still trying new things - the man's curiosity and inventiveness is still one of the world's wonders. It has the requisite number that's too stupid to be borne - "Fuh You" in this case - and he takes it upon himself to deliver a couple of messages for the people of earth ("People Want Peace" and "Despite Repeated Warnings.") Hey, John and George have both passed on, someone's got to do it. Otherwise, he's simply got some really good songs - "Caesar Rock," "I Don't Know" and "Dominoes" in particular.

8. Flaming Pie (May 1997)

McCartney had been distracted first by working on the Beatles Anthology project (and his wife's health problems.) He said one of the lessons he took away from his extensive look back at his own past was a reminder to raise his own standards. But McCartney had also needed a kind of emotional closure with his old band - he was the one who had always tried so hard to hold it all together, the one who never gave up on them, the only one who never quit until it all exploded at the end. He's in a ruminative mood here, interested in looking back more than usual, and this modest collection of quiet songs is a small triumph. The pounding title track, which refers to Lennon's famous explanation of how the Beatles got their name, is silly although one can't help but enjoy its relentless energy. The two semi-jams with Steve Miller sometimes seem a bit of an indulgence. Still, it had been almost twenty years since McCartney put so many good songs together at once. One of the sweetest moments is "Little Willow," his goodbye to Ringo Starr's first wife who had just died of cancer. (She's the Mo that Paul thanks at the end of the rooftop concert, after John hopes they passed the audition.)

7. New (Oct. 2013)

McCartney's remarkable 21st century hot streak continued after he passed his 70th birthday. Memory Almost Full had sounded very much like a man taking stock of his life and his legend - by McCartney's standards, it's a remarkably self-conscious and reflective piece of work. With New, he puts that sort of thing firmly in his rear view and produces the most vivid and modern pop music he can muster, bringing in no fewer than four young producers to help. It's not because he seriously expects to carve out his own place at the top of today's charts. He knows better than that. It's just that he's always been drawn to the rush and the excitement of whatever's happening now and he wants to get in on it, too. He has the energy of a man half his age, and of course he has more memorable melodies than anyone. The track that perhaps doesn't fit is "Early Days," a starkly recorded memoir of John and himself as young men. But even this makes its own kind of sense. McCartney refuses to accept the vast mythology that has grown up around his own history and insists on the primacy of the way he actually remembers it. He's insisting, in his usual oblique way, that he's a real person rather than something found in a museum. He's still a modern musician making modern music.

6. Chaos and Creation in the Backyard (Sep. 2005)

For this album, McCartney brought in Nigel Godrich, Radiohead's longtime collaborator and producer. It was a good idea - while confessing to being intimidated by working with a living legend, Godrich still found the gumption to challenge McCartney as no other producer save George Martin had ever been able to do. ("Very cheeky of him," said Paul). Perhaps we have Godrich to thank for the fact that McCartney's habitual, almost instinctive occasional lapses into cute whimsy seem to have all been peeled away. Godrich also preferred working with McCartney the one-man band than the bandleader, so most of these tracks feature just the two of them. It's not without its lively moments: the opening "Fine Line" is a hooky piece of energetic pop, "At the Mercy" moves along at a brisk enough pace, and the hidden track at the end, "I've Only Got Two Hands," begins as a stomping instrumental before veering off in several weird directions. But Godrich was looking for something else - it was apparently at his urging that the album's centrepiece, a comparatively lengthy meditation on a failed friendship called "Riding to Vanity Fair," was taken at a slower pace. (McCartney has always insisted that the song has nothing to do with Lennon, but it still sounds like a statement of how Paul felt about Lennon around 1970.) The gorgeous "Jenny Wren" sounds rather as if it was somehow omitted from the second side of the White Album. The album has one of his few covers that I actually like - it's a photo of a very young McCartney with his mother's washing hanging on the line above him. It was taken by Paul's brother Mike in their backyard; it must have happened sometime between Paul's 14th birthday in June 1956 (he got his first guitar soon after) and his mother's passing that October.

5. Memory Almost Full (Jun. 2007)

So what did Paul McCartney do when he finally turned 64? He went and made one of the finest albums of his career. There's practically a whole sub-genre now of aging rock stars considering their own mortality and while Memory Almost Full belongs among them, it's not a meditation on the approaching end so much as a celebration of the life that was lived. The prevailing mood is wonder - all this really happened? To me? So marvelous, so unexpected, all of it, from the boy playing with his bucket by the sea to the bloody Beatles. McCartney doesn't rage against the dying of the light - he's still delighted that the light was there in the first place. So he begins by exhorting us all to "Dance Tonight" and admits that he can't escape his "Ever Present Past." So along the way we'll have a silly love song ("See Your Sunshine"), a stomping rocker ("Only Mama Knows"), an eccentric character study ("Mr Bellamy") and then we'll have an attempt to remember something sweet that we've lost with time ("You Tell Me.") To an ex-lover McCartney has nothing to offer but "Gratitude," in one of the least recriminating breakup songs anyone has ever written. And when we come to "The End of the End" he wants jokes to be told and stories of old. It's a journey to a better place, and a better place will have to be pretty special because this one wasn't bad at all. No reason to cry, no need to be sad. Except it's not quite the end - let's have one last fierce, carnal rocker before we go. Just nod your head.

4. Ram (May 1971)

McCartney actually kicked off 1971 with a standalone single, "Another Day." The record was a success, going top ten in the UK and America but McCartney was criticized without mercy for his sympathetic portrait of a working girl wearied by the daily grind of her life. How bourgeois, sniffed the hip critics of the day. How irrelevant. Who cares? It wasn't a great song, but there's still something to be said for the generosity of spirit behind it. What other rock songwriter of the day would have even considered such a woman worth writing a song about? What other star would have even noticed her, even thought about her? The hip critics also took umbrage at McCartney crediting the writing of this song to Paul and Linda McCartney. Yoko Ono may have been weird, but she was known to be an artist, however strange and avant-garde - Linda McCartney was merely a photographer. McCartney would continue this practice on his next four albums as well. In truth, as Linda would always acknowledge, this was mostly a ploy to keep half the publishing in the family. Lennon and McCartney had finally lost the struggle to gain control of their own publishing but were still under contract until 1973. And so while Ram's reputation has steadily improved over the years ("the first indie pop album,") it was not well received in its moment. Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner was a Lennon fanboy, and in the early 1970s he seemed to make it his personal duty to denigrate McCartney and all his works, and that humble first album had certainly not delighted the multitude. McCartney is usually at his best when he has something to prove, and he took the need to make a real album seriously. He wrote some songs, he auditioned some players, he booked time in a real studio. Even so, it maintains something of a homemade, DIY feel much of the time. And McCartney was still insisting on writing about whatever he felt like writing about - the love of his life, the countryside, and domesticity, along with the usual bursts of whimsy. None of it sounds very ambitious except the closing "Back Seat of My Car," which tries to make a powerful drama out of his own version of two-lovers-vs-the-big-bad-world. He almost pulls it off, too, mostly out of sheer vocal willpower. McCartney even scored a hit with the bizarre "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey," which willfully joins three completely unrelated songs into an utterly incoherent whole - it became his first US number one (he didn't even release it as a single in the UK.) This is a fetching batch of songs - I especially like the casual rocker "Eat at Home" and the graceful "Heart of the Country" - it's just that something else was demanded of major rock stars at the time. Major statements were expected and McCartney was singing stuff like "I could smell your feet a mile away." Lennon, being Lennon, naturally thought much of the album was aimed directly at him. Very little of it actually was - the "Dear Boy" who never knew what he had found was Linda's first husband, the dog with three legs was just a piece of foolery. But "Too Many People" was indeed a shot across Lennon's bow, however mild and obscure. Lennon certainly heard it and it was what actually prompted "How Do You Sleep."

3. Tug of War (Apr. 1982)

In 1980, McCartney was getting tired of Wings and apparently unsure what to do next. He got together with George Martin, for the first time since they'd made Abbey Road eleven years earlier. Martin first insisted that McCartney work a little harder at the songwriting. They were actually in the studio together the day after Lennon was murdered - nothing was accomplished, as you can imagine. Work on the album proper began a few months later, at Martin's AIR studio on the Caribbean island of Montserrat (the studio was destroyed, along with much of the island, by Hurricane Hugo in 1989.) McCartney has a few famous guests - Stanley Clarke plays bass on two tracks, Ringo plays on another three. One song is a duet with Carl Perkins, two others with Stevie Wonder. But it's mostly Paul himself, with some help (for the last time) from Denny Laine. The beating heart of the record is a remarkable four song sequence in the middle. Lennon's ghost hangs heavily over the entire album - every time McCartney hints at nostalgia, regrets past conflict, asks for ease from any sorrow... one simply can't help but make assumptions as to what he's really referring to. But the one track that directly addresses his lost bandmate is the quiet "Here Today," as modest a remembrance as one could imagine. It's almost as if McCartney wanted to be sure that it wouldn't be a hit, that crowds couldn't sing along with it. It's too personal for that sort of thing, uncertain and halting, finally seeming to simply trail off into grief and silence. And so one flips the record over (that's what we did back in the day) to a pounding piano based rocker called "Ballroom Dancing," an exuberant recollection of the good times we used to have. This is followed by a very, very weird track about money losing its value - which suddenly veers off in a whole new direction, into a strange nightmare that ends with an impassioned scream of "it didn't happen..." which hangs in the air... and then the song resignedly returns to the state of modern currency. A little unsettling. And then comes "Wanderlust," a song based around one of those McCartney melodies that sounds as if its been lodged deep in the human cortex since before time began, a song so gorgeous that one can't possibly care what it might actually be about. I don't have a clue myself, and I've been listening to it with joy and wonder for almost forty years. The cumulative effect is stunning, so stunning that his trite duet with Stevie Wonder (and yet another number one), a cheesy bag of cliches called "Ebony and Ivory," almost sounds like its earned its right to conclude the record.

2. Band on the Run (Dec. 1973)

McCartney rallied from Red Rose Speedway with two very impressive singles - the James Bond theme "Live and Let Die," a bizarre mashup of musical motifs held together by little more than sheer musical muscle, and a catchy little rocker called "Helen Wheels" that so impressed his US record company that they slipped it on to the North American version of his next album. Which was the record that completely restored his reputation as a great and relevant artist. It was - naturally - made under extreme duress. The day before they departed to Nigeria to begin recording, his drummer quit the band. His guitar player had quit one week earlier. There had been an outbreak of cholera, and UK residents were urged to avoid Nigeria - the letter warning the McCartneys of this arrived at the office a day after they had already left for Africa. Upon their arrival, they discovered that EMI's local studio came nowhere up to acceptable standard, not even close. And to top it all off, Paul and his wife were robbed at knifepoint - he lost a bunch of demos and most of his song lyrics. So of course he made one of the best records of his life. McCartney is one of the most inventive deviser of melodies who has ever walked the earth, but even so the abundance of unforgettable melodies on this record is downright excessive. The opening title track - which gave him his third US number one - decoys the listener with two separate and distinct hooks, each quite capable of being the basis for its own song, before getting underway. He just throws them away. He's got so many. He doesn't need them. The tunes are so ridiculously great that one doesn't even notice that for the most part the lyrics are mostly just ridiculous. It simply doesn't matter. Ho? Hey ho? The Jailer man and Sailor Sam? What on earth is he talking about? "Jet" is fabulous, unforgettable, and it's four minutes of utter nonsense about... a dog, apparently. "Let Me Roll It" sounds like nothing so much as an affectionate pastiche of his estranged partner - from the snarling guitar riff right down to the reverb drenched vocal. Every song is memorable, every performance is distinctive and full of character. It's not a masterpiece, not a perfect album - as ever, McCartney is both too abundant, and too erratic to ever make such a thing. And much of it's simply nonsense. But it's glorious nonsense.

1. Run Devil Run (Oct. 1999)

I think this is as close to a perfect record as this most maddening, most inconsistent of artists has ever made. There are no weak songs, no bouts of weird whimsy, no self-indulgent experiments, no filler. The thing is, there are hardly any Paul McCartney songs - just three of them - and ultimately, that's kind of a problem. How can it truly be a great McCartney record without McCartney songs? But that's also the point of the whole project. In the wake of Linda's illness and death, McCartney got together with a couple of old friends - David Gilmour and Ian Paice in particular - and they recorded a dozen songs he remembered from his youth. He dealt with his loss and his grief by immersing himself in the songs that had made him love music in the first place, songs that made him move, that made him feel alive. And it's amazing. Hearing him tear into "Lonesome Town" or the Vipers obscure oldie - "I don't want no other baby but you" - with the love of his life gone forever is as intense and powerful as anything he's ever put on record. The whole record is like that. I don't know if he's ever sung with more passion, more feeling, and more freedom. The three original songs he mixes in fit perfectly with the rest - his title track is so wild it needs to be trapped and locked up. It probably helps that most of the songs are pretty obscure - McCartney and his players get to define them as they like. That said, the man takes on no less a titan than Elvis Presley ("All Shook Up" and "Party") and McCartney absolutely smokes the King himself. Just smokes him. Not even the Beatles had dared to take on Elvis.

JOHN LENNON

All of the Beatles grew into rather strange men - the unfathomably strange experience of being Beatles more or less guaranteed that - but John Lennon was a weird one from the beginning. As is generally known, he was a damaged little boy with genuine abandonment issues. His father had indeed abandoned his wife and child, and then his mother had given her little boy away to be raised by her sister. Lennon grew up a solitary child in his aunt and uncle's home. Lennon himself would emphasize that his was not a harsh upbringing - he was always comfortable, he was always with people who loved him and cared for him. But he'd been damaged, and he didn't want to be hurt anymore.

Lennon would spend much of his life lashing out at people, hurting them before they could hurt him. Lennon habitually denounced, in the bitterest terms possible, everyone who he thought had let him down; this was generally a list of everyone who had ever helped him, or tried to, along the way. And everyone just shrugged and said "that's John." When the Maharishi wasn't what Lennon hoped he was, he wrote the furious "Sexy Sadie" about him (the lyric originally went "Maharishi / you fucking cunt") - George Harrison played wonderful guitar as Lennon slimed someone George very much admired. (Paul and Ringo were fond of him as well.) Lennon's denunciations of McCartney have gone into rock'n'roll legend, but the very last interview of Lennon's life is extremely bitter about George, of all people. While Lennon had some cause to be angry with people like Allen Klein and Duck James, in no universe did the completely blameless Brian Epstein and George Martin deserve the share of abuse they received. The only person spared was Ringo, which probably tells you something about him.

I do think it's fair to say that the arrival of Yoko Ono broke up the Beatles. It was not her intention, and it wasn't because of anything she actually did. It was simply a matter of what she meant to John. He found something in her that he needed, desperately, something that he had found nowhere else in his life. I think it would be churlish for anyone to be unhappy about that. But Yoko Ono was an artist herself, and as such I don't think she was a good influence on Lennon at all. To oversimplify somewhat, it's Yoko's belief that some people are artists, and therefore whatever they do, by definition, is art. I don't think much of this kind of thinking at all. Self-expression is always self-expression, but it isn't necessarily art. Maybe it can be, but only sometimes, and certainly not by definition, automatically. But this was an idea that deeply appealed to Lennon, who was already in the habit of using his various artistic outlets to express his thoughts and feelings. In time, this was entirely what Lennon's art would consist of, and it would often stop being art at all.

Lennon recorded two albums in England, with the same cast of old chums George Harrison generally worked with - Harrison himself, Ringo Starr, Klaus Voorman, Nicky Hopkins. Then he moved to America. He made one awful record with Elephant's Memory, a mediocre local band - the rest of his work was done in big expensive studios with the best session players money could buy. While this suited Lennon's preferred ways of working - let's get it, now - the records generally have very little personality. This is the way of session musicians - they don't impose their own styles on the proceedings. So most of Lennon's solo career is slick, precisely performed studio rock. It lives or it doesn't entirely on the quality of the songs and the singing. While the singing was always up to the task - it was always John Lennon on lead vocal - far too often the songs weren't.

Lennon's solo career began while the Beatles were still a working band, with three standalone singles - the first "Give Peace a Chance" was more or less improvised in a Montreal hotel room and was only intended to provide the world with that catchy singalong chorus. He came back from his one-off live performance in Toronto, told his bandmates he was done with the Beatles, and immediately cut another single. That was "Cold Turkey," which has a great snarling guitar riff and an impassioned vocal, but little else worth remembering. And at the very beginning of the new decade, he made the marvelous "Instant Karma" with Phil Spector. It was written and recorded in a day, released within the week, and would turn out to be the best single of his career.

8. Some Time in New York City (Jun. 1972)

An abomination. Lennon and Ono had begun running with various leftist radicals and cranked out this collection of simplistic agitprop in support of a few causes of the day. It was just a detour, as it turned out. It still led nowhere. One track, "Woman is the Nigger of the World," manages not to be terrible. Which doesn't make it good.

7. Double Fantasy (Nov. 1980)